Experts believe the state still has high levels of immunity, likely making any possible surge caused by the omicron BA.2 variant less severe

Late last week, a key line on a chart tracking coronavirus case trends turned red, indicating something public health experts had not expected to happen so quickly: COVID infections appear to be on the rise again in Colorado.

So far, the increase has been modest, and it stems from one of the pandemic’s lowest levels of infection. It is uncertain whether the trend will last or whether the illnesses that occur as a result of it will be severe, though there are reasons to believe the answers to both questions are no.

However, it is happening at the same time that cases are increasing in other parts of the country and early warning signals from Europe are blaring. It’s also happening as the state backs away from its emergency response to the coronavirus, phasing out community testing sites that could provide a better sense of infection trends and changing hospital reporting requirements in a way that will give the strain less day-to-day visibility.

So far, here’s what we know.

Reported cases started rising again a week ago

Colorado reported only 74 new coronavirus infections on March 13, a Sunday, the lowest daily total since the pandemic’s inception. However, the number of reported cases has increased since then. By the 15th of March, the state had reported over 400 new infections.

More importantly, the increase is reflected in the state’s seven-day moving average of case counts, a critical metric that smooths out the daily peaks and valleys. On the 13th, the average was approximately 186 new infections reported per day. By Thursday, the daily average had risen to 250 new cases.

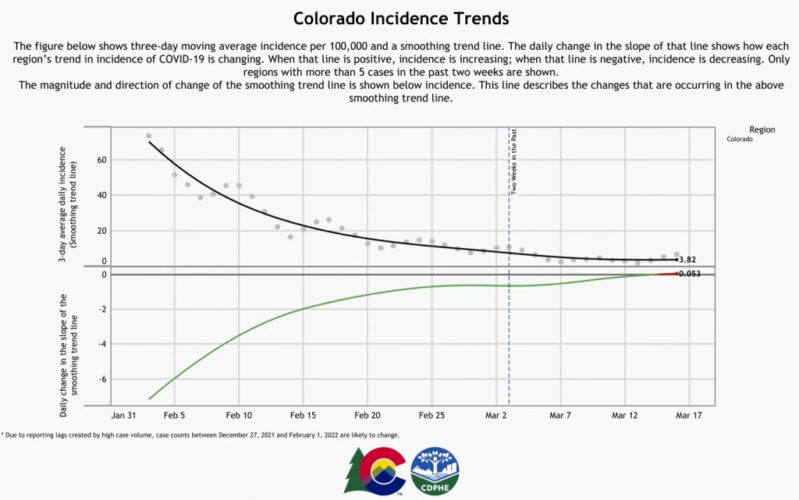

Colorado had seen an increase in cases for the first time in more than a month. The top line in the chart below shows the long declining trend that had, in recent weeks, flattened out.

The bottom line shows the daily direction of change. When the bottom line is green, it means that the number of cases is decreasing. When it turns red, as it did last week, it indicates that the number of cases is increasing.

However, the trend is not entirely clear. The number of COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital has not increased, nor has the percentage of coronavirus tests that are positive. These numbers are used to confirm infection trends.

In Colorado, monitoring for the presence of coronavirus in wastewater has not revealed a conclusive upward trend.

(All of these figures are current as of Thursday. The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment was unable to update the figures on Friday due to a system error, and the department typically does not update its data over the weekend.)

A new-ish variant is likely involved

A coronavirus variant that appears to be even more transmissible than omicron appears to be one of the causes of the apparent increases.

The variant is known as BA.2 — it doesn’t have its own Greek alphabet letter because it is technically a sublineage of the omicron variant, a cousin to the BA.1 omicron sublineage that moved through Colorado and the rest of the country earlier this year. According to studies, BA.2 is up to 80% more transmissible than BA.1, which was more transmissible than the delta variant, which was more transmissible than the alpha variant, which was more transmissible than the original form of the coronavirus.

“Omicron was this super-infectious variant, and this is more infectious,” said Beth Carlton, a professor of epidemiology at the Colorado School of Public Health who is a member of the state’s COVID-19 Modeling Group.

BA.2 was estimated to account for approximately 7% of new cases in the state as of the end of February — the most recent data available — up from less than 1% at the beginning of the month.

Places across the country and world are also seeing a rebound in infections

Overall, new infection reports continue to decline across the country. In New York, however, cases have increased by about 15% in the last two weeks. Officials in New York City estimate that BA.2 accounts for roughly 30% of new infections in the city.

Meanwhile, wastewater treatment plants across the country have begun to detect signs of rising coronavirus infections. Wastewater tracking is identified as a vital early-warning system for the country.

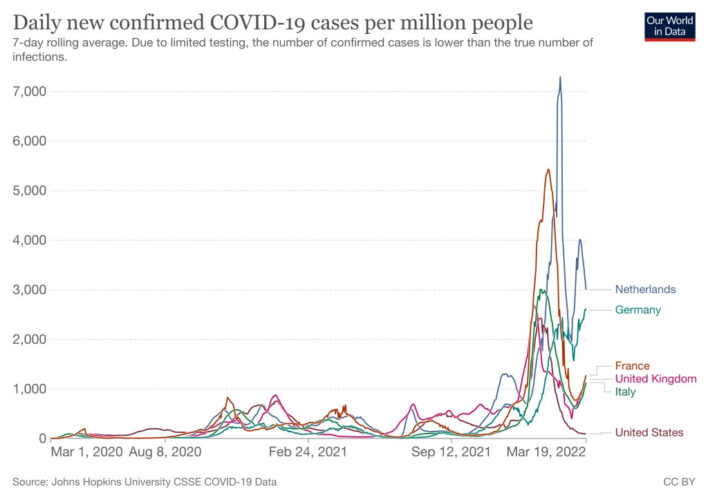

Most notably, several European countries have recently seen new spikes in cases thought to be caused by BA.2. France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom are all experiencing case surges, though they are still far below the peaks of their initial omicron waves.

European trends are frequently regarded as forebears of what is to come in the United States.

The Netherlands also saw an increase, but cases are now beginning to decline.

If a new wave hits, it may not be as severe

Much remains unknown, according to Carlton, as modelers try to adjust their forecasts for the emergence of BA.2. She did, however, express cautious optimism.

While the subvariant is more transmissible, it does not appear to cause more severe illness, nor does it appear to be any more effective at juking the immune system than omicron BA.1.

This means that people who have been fully vaccinated and boosted are more likely to be protected from becoming seriously ill. People who caught COVID during the first omicron wave are likely to be better protected this time. It could also imply that a BA.2-driven wave will be short.

“Is this going to lead to a crushing wave as we had in January?” she asked. “Probably not because so many people were infected, and we have such high levels of protection.”

According to Carlton and others on the state’s modeling team, approximately 90 percent of Colorado’s population is currently immune to COVID, either through vaccination or prior infection. That still leaves over 500,000 people vulnerable to an outbreak caused by a highly infectious variant.

Carlton, on the other hand, believes that such a surge would not endanger hospital capacity. Instead, communicating to people how to assess risk for themselves will be the “I think we’re out of the catastrophe phase,” she said. “But in this new phase, how do we inform people to make good decisions on how they protect their health?”

Colorado’s scaled-back approach may make it harder to understand a new wave

The state health department has announced that it will close its large community testing and vaccination sites by the end of the month in order to transition COVID services to traditional health care settings. During previous outbreaks, the testing sites were critical in verifying new infections.

In addition, the state has discontinued the distribution of at-home rapid COVID tests.

Furthermore, the state announced last week that hospitals will now report their COVID patient numbers twice weekly, with hospitalization figures available to the public on the state’s website updated only once per week.

“This reporting cadence provides CDPHE sufficient data to track important COVID-19 trends overtime during this stage of the COVID-19 response,” the agency wrote in a news release announcing the reporting change.

The changes in the state response show how much more responsible individuals will need to take in order to protect themselves and the community during any future infection surge. And, according to Carlton, that won’t be easy, because some people, such as those who are immunocompromised or live with someone who is, may remain vulnerable, while others may be able to resume a normal life.

“I think that’s the hardest part of the current phase we’re in,” she said.